These days, energy costs and environmental concerns being what they are, there is a great emphasis on building tight, well insulated, homes. To increase the energy efficiency of the home builders blanket the house with layers of thick insulation. And decrease the amount of air that infiltrates the home from the outside by covering it in house wrap. We go to great lengths to build green homes that are, in essence, as close to air tight bubbles as we can make them. But is this a healthy way to build? After all, if a house can’t breath, the people within it probably will struggle as well.

In fact, indoor air pollution has increased as homes have become more energy efficient and better insulated and many people suffer illness as a result. Indoor air pollution can be ten times worse than outdoor air pollution. Billions are spent annually to remedy the health costs of indoor air pollution. What do we mean by air pollution? It’s more than just stale air and cooking smells. Indoor air pollution consists of chemical gases from building materials, mold spores, mildew, pollen, oxides including carbon dioxide and monoxide, and radon just to name a few. If these contaminants can’t escape into the great outdoors, they will stay in the home, there for the inhabitants to breath over and over again.

What then to do?

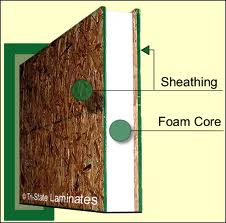

At Trilogy we take a multi-disciplined approach to improving the air quality within our homes. It is well known that Trilogy builds exceptionally well insulated homes. Structural Insulating Panels are used in many of hour homes to dramatically increase the energy efficiency of wall systems. Knowing that tight homes needed to find a way to breath, we have experimented over the years with various combinations of technologies. Now, all Trilogy homes include air quality improvement systems. Whole house humidifiers tied to air circulation and ventilation systems bring in fresh air and eject stale air constantly. As fresh air is brought in from the outside, it is humidified and purified as stale used air is ejected. Heat exchange systems insure that cold air is passively warmed before it enters the house. And that hot air is cooled before it enters the house.

So not only is Trilogy building the most energy efficient, tightest homes in the industry. It is also building homes that breath in pure clean air. The result is exceptional indoor air quality.